Words / Photos: Alex Wood

Friday night’s installment of the Chicago Bluegrass & Blues festival offered two very different takes on blending folk-rock and country.

To the surprise of many, the presumed headliner Justin Townes Earle came out before The Felice Brothers.

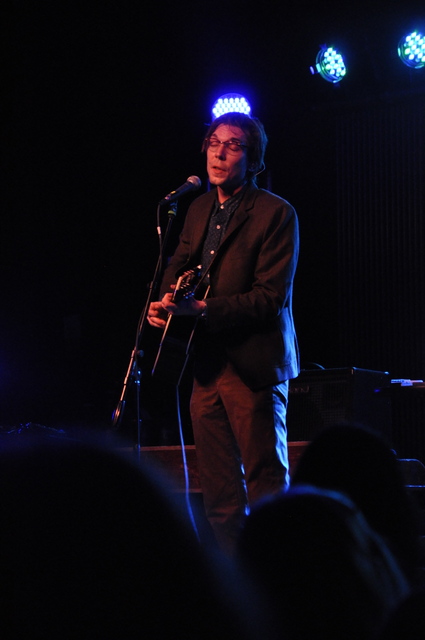

Paul Niehaus added sparse electric and slide guitar backing, making Earle’s band two members short of last year’s tour. This made for a comfortable, laid-back set, loose and informal in feel.

Playing heavyweights like “Memphis In The Rain” and “Harlem River Blues” early in the set, Earle left room for surprises throughout the setlist. “Harlem River Blues” was performed in an almost eerie, minimal fashion, slowed down to no longer feel like the upbeat, sing-along studio version.

But perhaps the biggest surprise was the announcement of an upcoming double LP being held back by label troubles.

Earle performed two new tracks throughout the evening, one dedicated to Billie Holiday and another with the autobiographical refrain, “single mother, absent father, broken heart.” Both featured the combination of poignant, meaningful lyrics with stripped-down folk delivery -- all that fans could hope for in new Earle tracks.

Nearly every song featured heartfelt commentary from Earle, a standard practice at his shows.

His childhood and abandonment by father Steve Earle came up before “Mama’s Eyes,” the songwriter commenting that his mother was everything to him.

“I was a young man when/ I first found the pleasure in the feel of sin/ And I went down the same road as my old man/ Yeah, I was younger then,” he sings with touching sincerity.

Yet the majority of the audience talked through the set, chatter often rising to an equal or greater volume as the music. The performers didn’t let it faze them.

Earle spoke of the festival’s essence, referring to his appreciation of “proper country music… not what’s made today.” The kind, he said, made by “people having fish-fries.”

“Forget about what you learned in church, I’m gonna take you to the other side of town,” he said with a laugh before breaking into “Ain’t Glad I’m Leaving,” a perfect blend of blues and the “proper country” he spoke of prior.

Niehaus left halfway through the set, leaving Justin Townes Earle to perform solo.

Earle played an unbelievably passionate performance of Lightnin’ Hopkins’ “Been Burning Bad Gasoline,” swaying side-to-side and moving about stage between verses, each line delivered with a coarse, bluesy vocal delivery that finally managed to silence the talkative crowd for a few minutes.

His advice for such a performance?

“Practice… Smoke a lot of weed and just sit down and play that guitar,” he joked afterwards.

After three acoustic songs Niehaus returned for the rest of the shortened set, which closed with “Rogers Park,” a track about the far-north Chicago neighborhood.

“This one’s to old Rogers Park,” he said. “I think they just pissed it all up to Evanston.

The song’s imagery of smoking out of windows, the red line and snow off the lake provided an especially intimate feel, clearly saved to close the show with meaningful purpose.

And with that, Earle’s set was suddenly over.

The front of the crowd dispersed, a large portion leaving, and those in the back moved up. Despite Justin Townes Earle having been promoted as the headliner, The Felice Brothers had a sizeable fan base present.

As the five-piece band played their take on traditional tracks like “Cumberland Gap” and “Hesitation Blues,” their folk-rock formula was unmistakable.

The Felice Brothers are the kind of band that sound good as a whole without doing much individually, favoring simple chord progressions played in unison above all else, using violin, keys and accordion to beef up their sound.

The crowd danced to the loud accordion stomp of “Cumberland Gap,” and sang along to “Whiskey In My Whiskey,” a song about what it sounds like.

Lyrics stuck to themes that traditionally appear in Americana music. The band traded vocals amongst members, singing about highways, country music, train whistles, the devil and every Southern state on the map.

Though occasional tracks pushed the band in new directions, such as the loud and abrasive “Cus’s Catskill Gym,” the band largely played it safe, the remaining crowd never seeming to mind.

The performers jumped off the drum stand, shared microphones for shaky harmonies, traded instruments and threw themselves about stage, dancing when not playing. The band was clearly here to entertain and seemed to be doing just that, and perhaps this was more fitting for the drunken, talkative crowd.